Problem:

Problem:A ideal spring has an equilibrium length. If a spring is compressed, then a force with magnitude proportional to the decrease in length from the equilibrium length is pushing each end away from the other. If a spring is stretched, then a force with magnitude proportional to the increase in length from the equilibrium length is pulling each end towards the other.

The force exerted by a spring on objects attached to its ends is proportional to the spring's change in length away from its equilibrium length and is always directed towards its equilibrium position.

Assume one end of a spring is fixed to a wall or ceiling and an object pulls or pushes on the other end. The object exerts a force on the spring and the spring exerts a force on the object. The force F the spring exerts on the object is in a direction opposite to the displacement of the free end. If the x-axis of a coordinate system is chosen parallel to the spring and the equilibrium position of the free end of the spring is at x = 0, then

The proportional constant k is called the spring constant. It is a measure of the spring's stiffness.

When a spring is stretched or compressed, so that its length changes by an amount x from its equilibrium length, then it exerts a force F = -kx in a direction towards its equilibrium position. The force a spring exerts is a restoring force, it acts to restore the spring to its equilibrium length.

Problem:

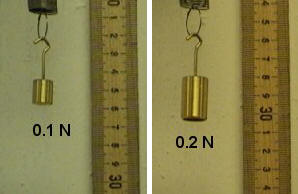

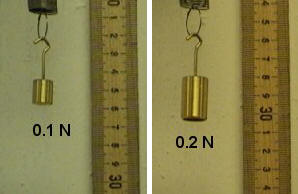

Problem:A stretched spring supports a 0.1 N weight. Adding another 0.1 N weight, stretches the string by an additional 3.5 cm. What is the spring constant k of the spring?

You want to know your weight. You get onto the bathroom scale. You want to know how much cabbage you are buying in the grocery store. You put the cabbage onto the scale in the grocery store.

The bathroom scale and the scale in the grocery store are probably spring scales. They operate on a simple principle. They measure the stretch or the compression of a spring. When you stand still on the bathroom scale the total force on you is zero. Gravity acts on you in the downward direction, and the spring in the scale pushes on you in the upward direction. The two forces have the same magnitude.

Since the force the spring exerts on you is equal in magnitude to your weight, you exert a force equal to your weight on the spring, compressing it. The change in length of the spring is proportional to your weight.

Spring scales use a spring of known spring constant and provide a calibrated readout of the amount of stretch or compression. Spring scales measure forces. They determine the weight of an object. On the surface of the earth weight and mass are proportional to each other, w = mg, so the readout can easily be calibrated in units of force (N or lb) or in units of mass (kg). On the moon, your bathroom spring scale calibrated in units of force would accurately report that your weight has decreased, but your spring scale calibrated in units of mass would inaccurately report that your mass has decreased.

Spring scales obey Hooke's law, F = -kx. Hooke's law is remarkably general. Almost any object that can be distorted pushes or pulls with a restoring force proportional to the displacement from equilibrium towards the equilibrium position, for very small displacements. However, when the displacements become large, the elastic limit is reached. The stiffer the object, the smaller the displacement it can tolerate before the elastic limit is reached. If you distort an object beyond the elastic limit, you are likely to cause permanent distortion or to break the object.

The elastic properties of linear objects, such as wires, rods, and columns which can be stretched or compressed, can be described by a parameter called the Young's modulus of the material. Before the elastic limit is reached, Young's modulus Y is the ratio of the force per unit area F/A, called the stress, to the fractional change in length ∆L/L. (This is an equation relating magnitudes. All quantities are positive.)

Young's modulus is a property of the material. It be used to predict the elongation or compression of an object before the elastic limit is reached.

Consider a metal bar of initial length L and cross-sectional area A. The Young's modulus of the material of the bar is Y. Find the "spring constant" k of such a bar for low values of tensile strain.

Consider a steel guitar string of initial length L = 1 m and cross-sectional area A = 0.5 mm 2 .

The Young's modulus of the steel is Y = 2*10 11 N/m 2 .

How much would such a string stretch under a tension of 1500 N?

In order to compress or stretch a spring, you have to do work. You must exert a force on the spring equal in magnitude to the force the spring exerts on you, but opposite in direction. The force you exert is in the direction of the displacement x from its equilibrium position, Fext = kx. You therefore do work.

or

Work = area under the curve = width * average height

= (x2 - x1)*k(x2 + x1)/2 = ½k(x2 2 - x1 2 ).

The average force you exert as you change the displacement from 0 to x is ½kx.

The work you do when stretching or compressing a spring a distance x from its equilibrium position therefore is W = ½kx 2 .

When a 4 kg mass is hung vertically on a certain light spring that obeys Hooke's law, the spring stretches 2.5 cm. If the 4 kg mass is removed,

(a) how far will the spring stretch if a 1.5 kg mass is hung on it, and

(b) how much work must an external agent do to stretch the same spring 4 cm from its unstretched position?

If it takes 4 J of work to stretch a Hooke's law spring 10 cm from its unstretched length, determine the extra work required to stretch it an additional 10 cm.